Context

- What is this?

- This module describes what syntax means, and the syntax used to describe syntax.

- Why is this important?

- On the path to learning how to program, understanding and applying the syntax of a programming language is important. Instead of using a “loose” pseudocode syntax, it is more efficient to “learn the real thing” from the get-go!

- How is this done?

- This is accomplished by using a meta syntax language.

Syntax

Syntax is grammar for programming languages. The importance of syntax is the same as grammar for natural languages: it facilitates the proper parsing and understanding of program code.

Unlike natural languages, however, programming languages have relatively simple rules. This may make it seem easy to learn a programming language. The difficulty of learning and using a programming language is that the computer needs a program to match the syntax exactly to be understood. In the case of two humans talking in a natural language, many minor grammatical mistakes do not significantly impede communication.

As a result, the syntax of a programming language needs to be specified with precision.

Meta syntax

The syntax of a programming language is like the grammar of the programming language. Some form of meta syntax often specifies these rules. The word “meta” in this context means “one level more abstract”, derived from the Greek word that means “beyond.” In other words, meta syntax specifies the rules of the syntax of a language that describes the syntax of a programming language. The syntax of a programming language specifies what constitutes the correct ordering and structuring of code.

One commonly used meta syntax is called BNF (Backus-Naur form).

The syntax of C++ is intermediate compared to other programming languages. A plain BNF description of C++ can be difficult to follow. However, a BNF description that makes use of hyperlinks is considerably easier to follow for reasons that will be discussed later. Fortunately, Alessio Marchetti has already created a hyperlinked BNF description of the syntax of C++.

How to read the BNF notation

The basics

Each syntactic rule (also called a “production”) consists of two parts:

- the token being defined

- what the token can be expanded to

Let us consider the following example. An iteration-statement is describe as follows:

| token | expansion |

|---|---|

iteration-statement |

while ( condition ) statementdo statement while ( expression ); for ( for-init-statmentconditionopt ; expressionopt ) statement for ( for-range-declaration : for-range-initializer ) statement |

In this syntactic rule, the token iteration-statement has four alternative expansions, as each line of the “expansion” column is one alternative. In each expansion alternative, anything that is boldface must be entered verbatim, while anything not in boldface is a token with its own expansion. The subscript “opt” designates the token to be optional. Optional means the same as zero or one occurrence.

Essentially, a token (italicized and not boldfaced) is a placeholder. A placeholder can hold the place (a position in a sequence) of nothing or many components. A boldfaced item is also known as a “terminal”, a terminal specifies the text expected verbatim.

In a way, you can see a token instance as a folder, whereas a terminal instance is a file. This analogy cannot capture the sequencing of tokens and terminals in the expansion of a token. However, the folder/file analogy does capture the concept of hierarchy.

Returning to a statement made earlier, the BNF that makes use of hyperlinks is easier to read because each token is a hyperlink to the rules that specify how that token can expand. Compared to using a lengthy table of productions and relying on human eyes to scan and locate productions based on the left-hand side of the ::= symbol, hyperlinks are more interactive and easier to apply.

Alternative BNF meta syntax

Depending on the medium (file format), italic and boldface may not be viable options. This is especially the case when syntax needs to be described in a plain-text file. In this case, the convention is that quotes enclose terminals, whereas tokens appear without special punctuation marks.

Another plain-text BNF represents tokens using the < and > symbols to enclose the token identifier; terminals are unmarked.

Let us examine the three meta syntax rules as examples. The production being expressed is that the terminal “Johnny” can be parsed as a “person” token.

- Using boldface and italic:

person::= Johnny- This format is more visual and is generally easier to read. However, it requires the ability to format and display boldface and italic fonts.

- Using quotes: person ::= “Johnny”

- This format is generally the best option if there is no way to format or display boldface and italic fonts. Because only terminals are quoted, meta symbols such as

::=and|used in the meta syntax itself are clear.

- This format is generally the best option if there is no way to format or display boldface and italic fonts. Because only terminals are quoted, meta symbols such as

- Using brackets: <person> ::= Johnny

- This format can be more confusing because the terminals are not quoted. It becomes an issue if the syntax to be expressed uses symbols that are already being used in the meta syntax. For example, suppose the vertical bar

|is also a terminal. In that case, there is no way to differentiate between the meta syntax use and being a terminal in the language being specified. - This format can also be tricky to enter, depending on the editor and file format. Angle brackets are used in HTML, and by extension, Markdown. To display angle brackets, they need to be “escaped”, which adds complexity.

- This format can be more confusing because the terminals are not quoted. It becomes an issue if the syntax to be expressed uses symbols that are already being used in the meta syntax. For example, suppose the vertical bar

- Using brackets for tokens and quoted terminals: <person> ::= “Johnny”

- This is a good combination of the two simple formats, plain text-friendly.

- This format has the same potential problem of needing to “escape” the angle brackets in HTML and Markdown.

The reading modules of this class use the boldface and italic format. However, from a learner’s perspective, it may be easier to use the quoted terminal method. Avoid the use of the angle bracket method.

Repetition

BNF can be used to express the repetition of a pattern. Let us consider the syntactic rule of a statement-seq (statement sequence):

| token | expansion |

|---|---|

| statement-seq | statement statement-seq statement |

This shows that there are two alternatives to expand a statement-seq token:

statement: the first alternative is a simpler token, a single statement.statement-seq statement: the second alternative specifies a statement sequence, followed by a single statement.

When a token can expand to a sequence that includes one or more instances of itself, the definition is “recursive.” On the other hand, if a token can only expand to terminals or other tokens, it is called a “base case.” There are complicated cases of indirect recursive definitions where the recursive inclusion of the token being expanded is not in a single production, but indirectly through the expansion of multiple productions. A recursive production (syntax rule) is what allows input sequences that may contain pattern repetitions.

An example

The productions

Let us consider an example that does not relate to a complex programming language. For brevity, we will use the following notation:

token1 ::= token2 blah

The above example is a rule to expand token1 to token2 followed by the word “blah” verbatim. You can consider the symbol ::= to mean “can expand to”.

With this notation, we now define the following rules:

- R1:

friend::= Ali - R2:

friend::= John - R3:

friend::= Chang - R4:

friends::=friend - R5:

friends::=friendsandfriend

Note that R1, R2, and R3 are alternatives to expand friend, they are all base cases. R4 and R5 are alternatives to expand friends. R5 specifies that the token friends expands to a sequence that has another friends token instance, therefore R5 is “recusive.” A more concise way to represent the same set of rules is as follows:

friend::= Ali | John | Changfriends::=friend|friendsandfriend

In this concise representation, the vertical bar symbol | is used to separate the alternatives to expand the token on the left-hand side of the “::=” symbol. While more concise, this syntax specification does not identify the individual productions R1 to R5.

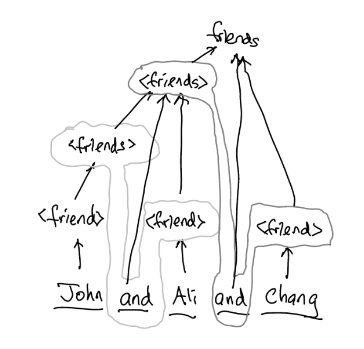

Let us consider how the sentence “John and Ali and Chang” is considered syntactically correct as the token friends.

The steps

- After processing the word “John”, R2 fires and recognizes that this is a token

friend. In the parsing of an input sequence, a rule “fires” means the right-hand side of the rule (to the right of::=) is recognized, and the recognized part of the sequence is now considered to be a token instance of the left-hand side (to the left of::=) of the production. - R4 can also now fire and recognize that we also have a

friendstoken. - The next word is “and”, R5 is a candidate to fire, but we need another

friendtoken in order for R5 to fire. - The next word is “Ali”, R1 fires, recognizing “Ali” matches the

friendtoken. - At this point, we have a token instance of

friendsrepresenting “John” in the input sequence, the terminal “and” is after thisfriendstoken instance, and we have a*friend* token instance representing “Ali” in the input sequence. - R5 now completes its firing because there is a

friendstoken recognized in step 2, a verbatim “and”, and afriendtoken recognized in step 4. As R5 fires, now we have a newfriendstoken instance recognized for the partial text of “John and Ali”. - The next word is “and”, R5 is a candidate to fire, we need another

friendtoken. - The next word is “Chang”, R3 fires, we just recognized another

friendtoken. - R5 now completes its second firing because there is a

friendstoken (corresponding to “John and Ali”), a verbatim word “and”, and also afriendtoken corresponding to “Chang”. We now have anotherfriendstoken recognized to represent the entire text of “John and Ali and Chang”.

Plain text syntax tree

Using plain text, the token expansion and structure (also known as a syntax tree) of the sequence can be viewed as follows:

friends

├── friends

│ ├── friends

│ │ └── friend → "John"

│ ├── "and"

│ └── friend → "Ali"

├── "and"

└── friend → "Chang"

Simple text syntax tree

This plain text “graphical” representation relies on the use of “box” characters. The following “simple text syntax tree” is an alternative method to show the hierarchy of token instances.

friend("John") represents that the sequence “John” is recognized as an instance of the friend token. Likewise, friends(friend("john")) shows the hierarchy that a friends token expands to a friend token (as per rule R4), the friend token, in return, expands to the terminal John as per rule R2. As a result, the above diagram using box characters can be represented as the following “simple text syntax tree”:

friends( friends( friends(friend("John")), "and", friend("Ali") ), "and", friend("Chang") )

This representation can be broken into multiple lines with indentation for clarity:

friends(

friends(

friends(friend("John")),

"and",

friend("Ali")

),

"and",

friend("Chang")

)

Parsing graph

Graphically, we can represent the parsing of the input sequence as follows:

flowchart LR

john[John]

and1[and]

ali[Ali]

and2[and]

chang[Chang]

friend1(friend)

friends1(friends)

friend2(friend)

friends2(friends)

friend3(friend)

friends3((friends))

john-->and1

and1-->ali

ali-->and2

and2-->chang

john-.-> friend1

friend1-.-> friends1

ali-.->friend2

friends1-.->friends2

and1-.->friends2

friend2-.->friends2

chang-.->friend3

friends2-.->friends3

and2-.->friends3

friend3-.->friends3

In this diagram, solid arrows indicate the flow in the text to be processed, “John and Ali and Chang”. Dotted arrows indicate the recognition of a token (think of these arrows as “reversed expansion”).